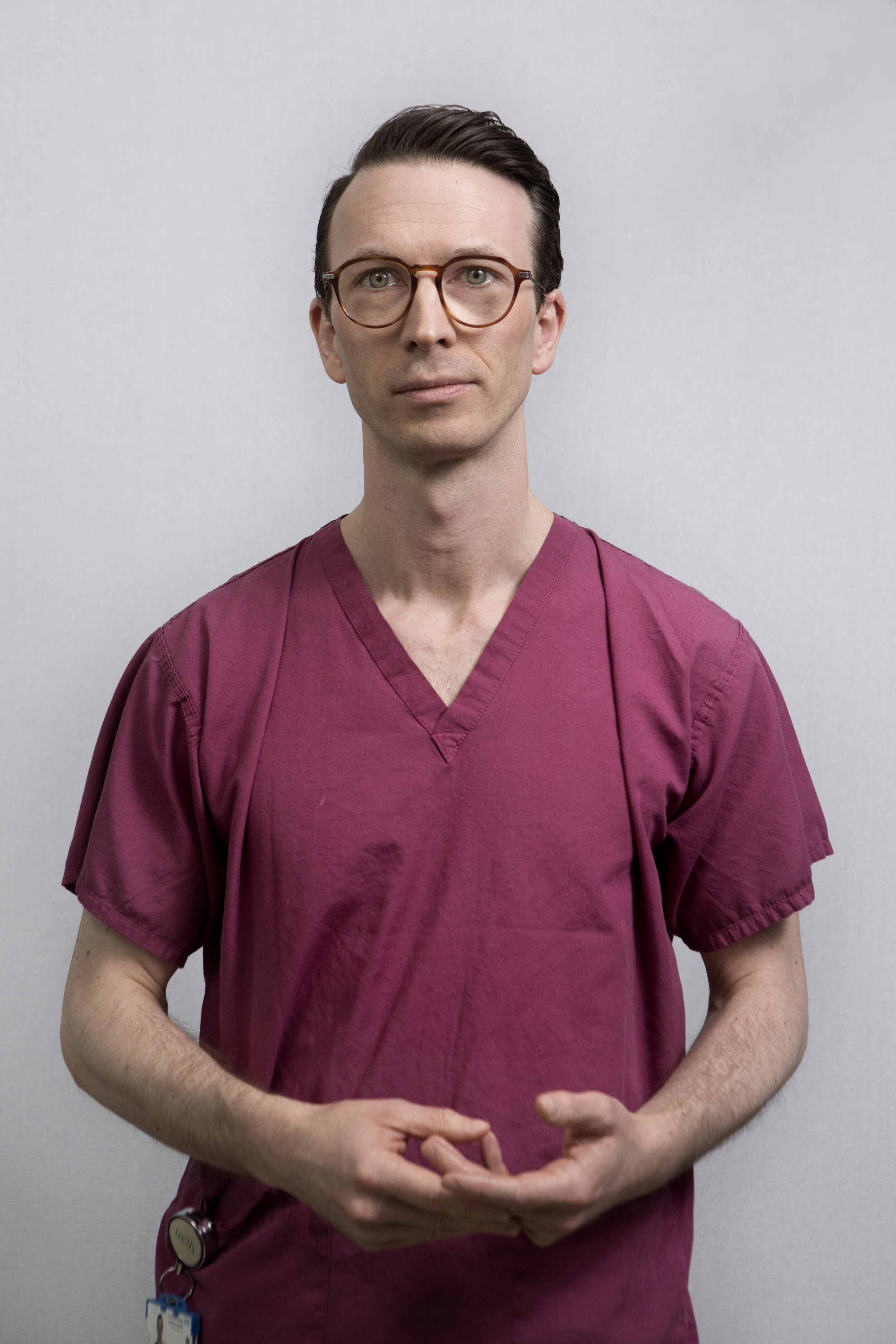

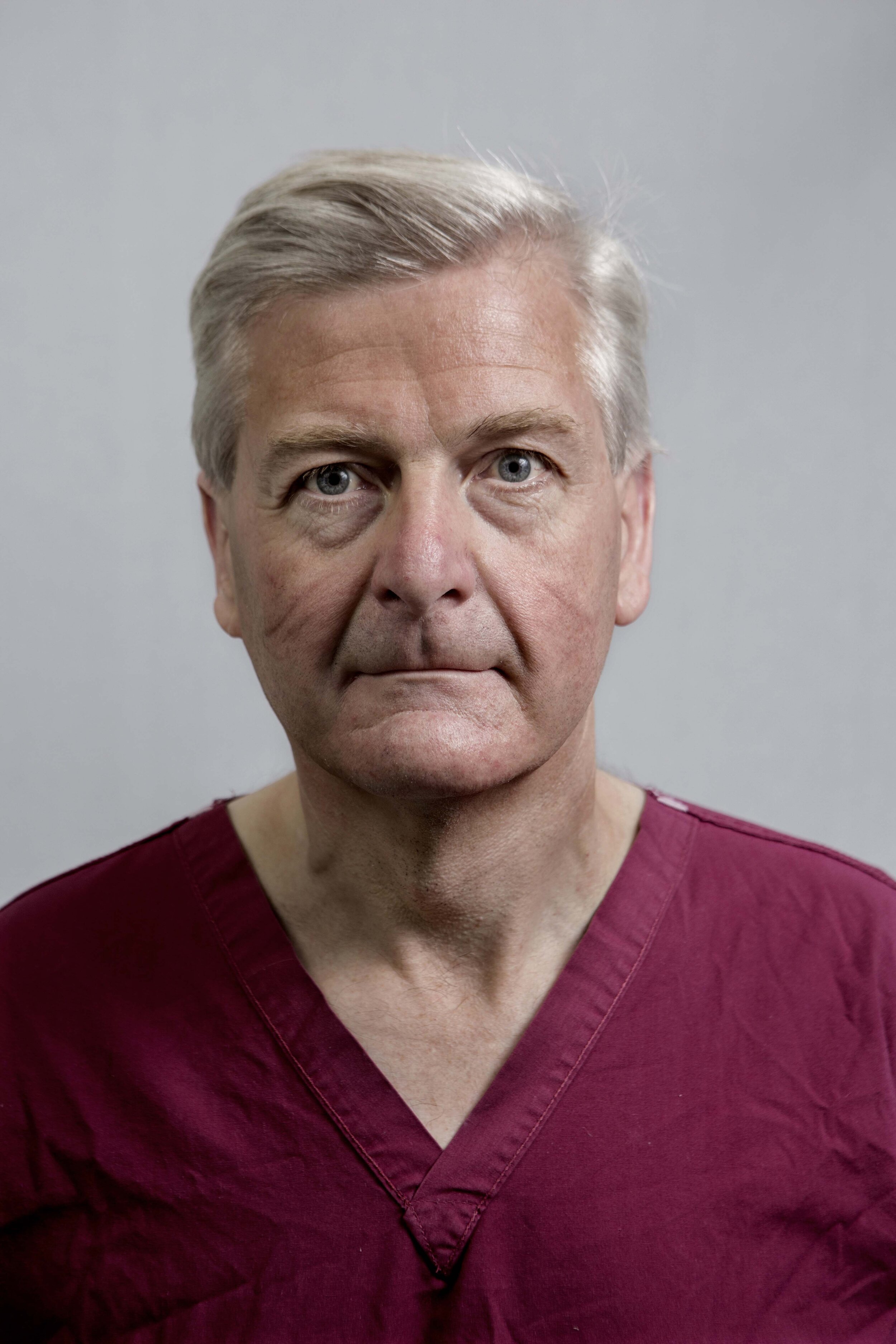

On a hot day in late spring, London’s University College Hospital is taking a deep breath. It is struggling through Covid-19 and is hastily taking stock, learning lessons from its successes and also counting its dead – those it could not save, both patients and staff. Like all hospitals, it is also bracing itself for the next big onslaught.

The diverse collection of professionals that make up its staff is buoyed by the public’s response, still running on adrenaline, but now also in a reflective mood. Dealing with Covid-19 has left some professionally invigorated and inspired. But, for others, working alongside constant death for weeks on end has been a deeply troubling experience. As one staff nurse said to me while having her photograph taken, “I still see the dead.”

“Humbled, exhausted-but fulfilled.”

“The pandemic has been tough – for the hospital and, of course, for our patients and their families – but, in some ways, it’s also been exciting and rewarding. All my career, I’ve rarely seen such leaps in medical care, particularly when it comes to treating people online – or ‘telemedicine’, as we call it.”

“It is hard not to be able to be close to patients. We only have our eyes.”

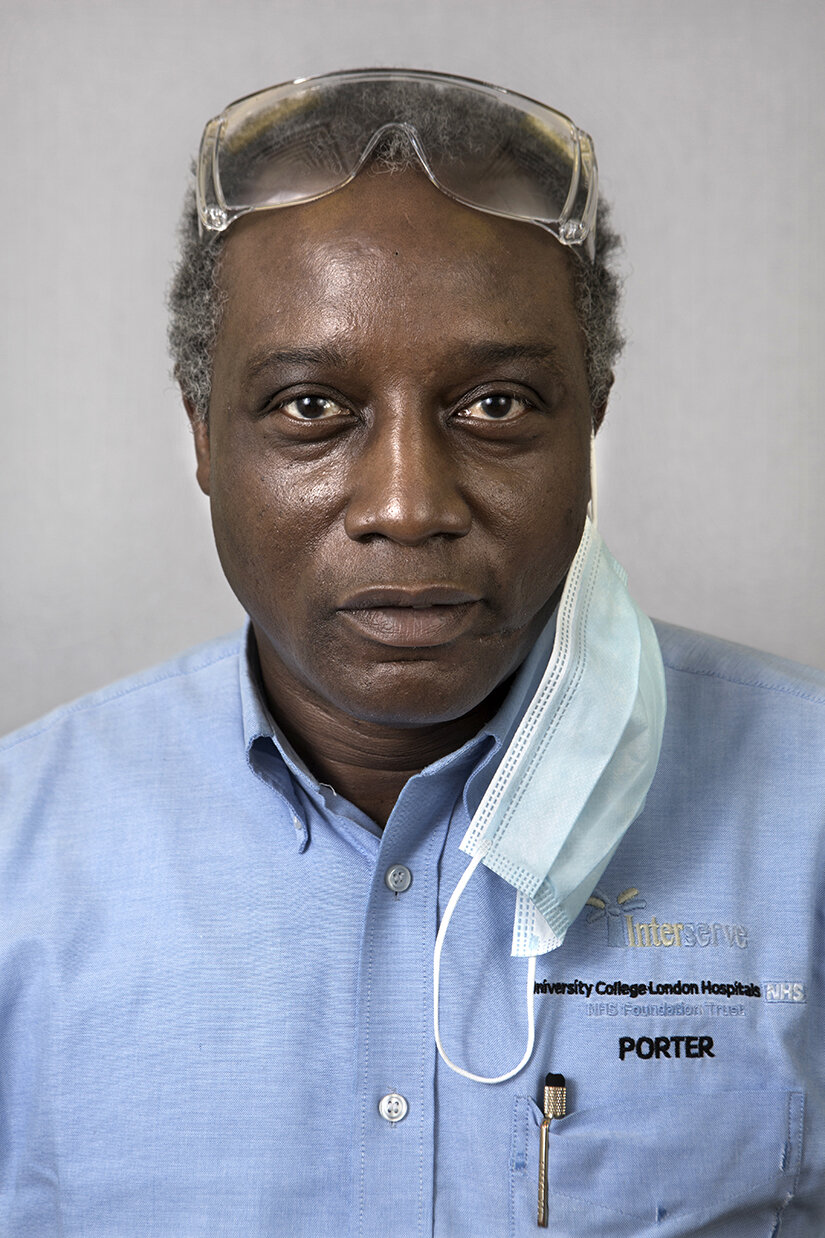

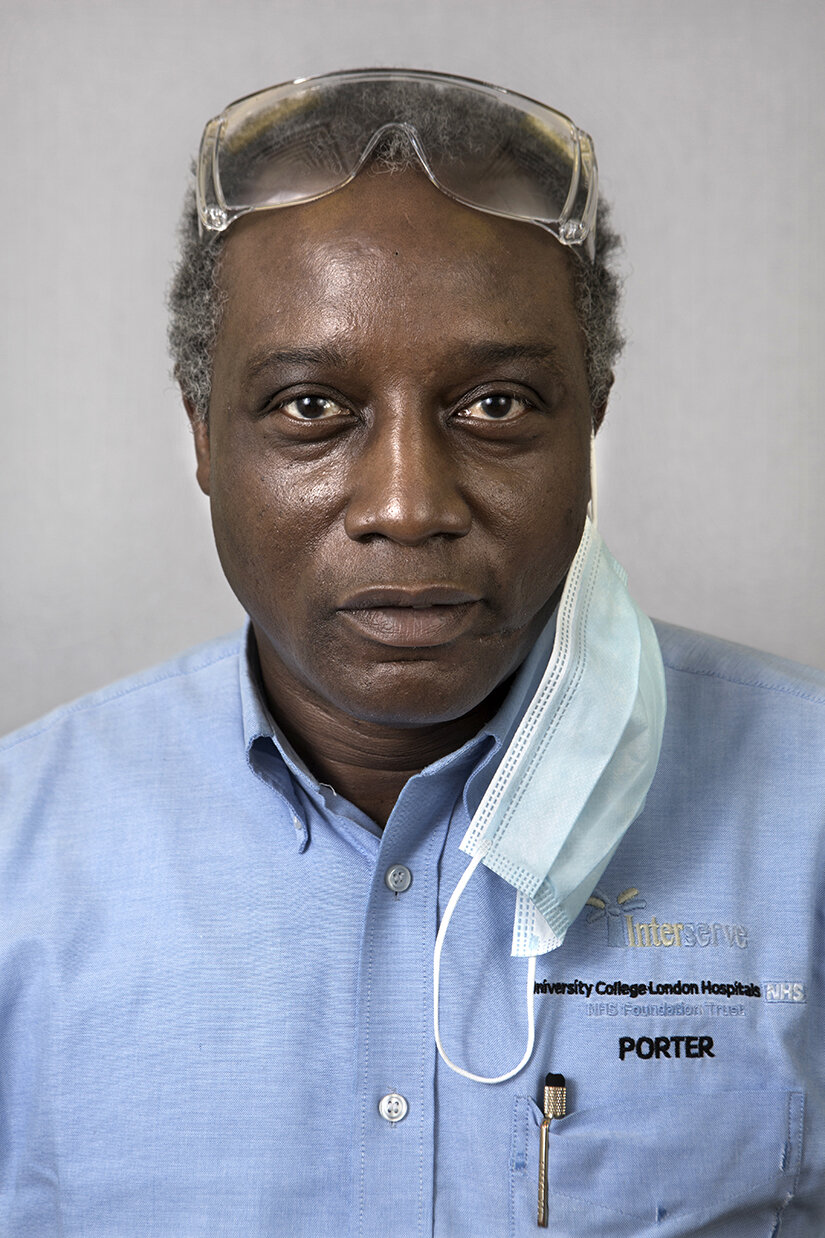

“I said no to staying at home. I’m feeling good helping those that need it.”

“Small things are important. A patient said, while looking at me in my PPE, ‘I recognise your eyes’.”

“A phone call on Friday afternoon, and, nine days later, the unit was up and running. A universe away from our previous work.”

“One Covid-19 patient stays in my mind. I was able to care for and stay with her until she died. She was 68 and we were her family. Helping her husband was so hard. This has made me more resilient but, at the same time, more compassionate to my ‘patient family’. Britain seems more compassionate. Oh, and I love The Clap!”

“Enjoy every day. Life is nothing; it can end so easily. Be kind and generous.”

“I feel emotional about my patients. I am strong at hiding my feelings from colleagues and family, but sometimes in the shower, at home, that’s when I cry. In normal times, I like doing patients’ hair, helping them shower, cutting their nails. Because of Covid-19 this wasn’t possible. But I tried to keep them comfortable, to moisturise their skin, to cry with them and to give their hand a little squeeze. I know I did the best I could for them all.”

“Many patients have had tracheotomies. I give them a voice, a means to communicate. On waking from sedation, we asked one patient what he would like to drink first and he whispered, ‘organic, M&S lemonade, please’. Always sticks in my mind.”

“I can’t sleep. What if I catch it and bring it home? [My family] say ‘don’t go,’ but I have to go. We argue, and I am in tears on the bus. My best friend died of Covid-19 in three days.”

“We found that many of our Covid-19 patients deteriorated faster than we could keep up with, and this was before we necessarily understood just how quickly the disease could affect them. I distinctly remember one woman who looked terrified, and it’s because she knew she was about to die. What still upsets me is how little time we had to make her comfortable.”

“So happy to see people going home.”

“When you are able to make a human corridor of applause for a patient who was supposed to die, it is something special. As one walked out, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘has her son put the dinner on?’”

“I’m no hero. I’m someone who’s lucky enough to work in the best profession there is for me.”

“I lost a friend and a family member to Covid-19. It is heavy, but you have to keep going. I wouldn’t do anything else.”

“Just now, my patient walked out of critical care to his physio. I was with his daughter; we watched him walk and his face turned to us – a great moment.”

“At the start of the pandemic, UCL took the decision to release all their clinical staff from academic and research responsibilities, in order to staff hospitals. This is all about teamwork, putting others first and doing the right thing. It is a vocation.”

“In our PPE, we must have looked like aliens to our patients. That was tough.”

“People are dying with no build up to death, no ability to have conversations and to say goodbye when they go into critical care. Even as a hardened professional, this has been difficult.”

“Fear, uncertainty, teamwork and collaboration.”

“I led the strategic incident management meetings, so I was painfully aware of the impact the virus was having on our patients, their families and our staff. But seeing the impact close up was very different. When I went to the wards to check in on our staff, I felt it – the temperature, the anxiety and the sights. Some patients were nursed in a prone position, face down to help their breathing. The inability to see their faces affected me greatly. I was angry with this virus, and could feel the weight of the concern and loss we bore on behalf of their families who were absent.”

“On my first shift in critical care, I looked after a patient whose wife was with him. Afterwards, when she took off her PPE, my hair stood on end – I recognised her as the wife of a dear friend from years ago who was now lying in the ward we had just left. Holding on to my emotions until I got home, I couldn’t stop crying.”

“In all my years of nursing, I have never felt so scared. There were parallel feelings of fear and duty. But I was so glad to be in the NHS for this experience. And to be among the fantastic medical minds at UCLH.”

“I am asthmatic and, walking in on the first day, I was so scared. I am more confident now.”

“I am scared, but I try to keep on working.”

“Now it is calmer, but when I walk through the wards I still see the faces of the patients from the peak. Some made it; others didn’t. I have flashbacks.”

“I am humbled. No matter who you are, you are affected by this disease. I am missing my cancer patients.”

“This is busy, demanding and you have to be on the ball. But seeing a patient who you thought was in trouble walk out of the ward, that gives you great pride.”

“It’s been hard, but we have all worked hard together.”

“I was so stressed to begin with. Now, I’m ok. It’s good to be appreciated.”

“Things that would normally take five years have been done overnight. All staff have shown such innovation.”

“15 months ago, I was a teacher. It’s tough now, but I’m so glad I changed.”

“The public reaction to the NHS was amazing. Sometimes you forget, and we needed that pat on the back. I want this to have a legacy.”

“It’s hard living among the dead on a daily basis.”

“I’m so happy to be here, even with Covid-19 about. I get true energy and happiness from my work, which I transfer to my family when I go home.”

“In the beginning, it was hard. We were watching Italy – where I’m from – and knew what came next. But we could prepare. We worked through history and it changed our lives.”

“I saw people dying almost every day. It has changed me. I am stronger, I am no longer scared of Covid-19.”

“It’s important for everyone to do their job.”

“When Covid-19 hit it awoke our compassion. We had become a bit desensitised.”

On a hot day in late spring, London’s University College Hospital is taking a deep breath. It is struggling through Covid-19 and is hastily taking stock, learning lessons from its successes and also counting its dead – those it could not save, both patients and staff. Like all hospitals, it is also bracing itself for the next big onslaught.

The diverse collection of professionals that make up its staff is buoyed by the public’s response, still running on adrenaline, but now also in a reflective mood. Dealing with Covid-19 has left some professionally invigorated and inspired. But, for others, working alongside constant death for weeks on end has been a deeply troubling experience. As one staff nurse said to me while having her photograph taken, “I still see the dead.”

“Humbled, exhausted-but fulfilled.”

“The pandemic has been tough – for the hospital and, of course, for our patients and their families – but, in some ways, it’s also been exciting and rewarding. All my career, I’ve rarely seen such leaps in medical care, particularly when it comes to treating people online – or ‘telemedicine’, as we call it.”

“It is hard not to be able to be close to patients. We only have our eyes.”

“I said no to staying at home. I’m feeling good helping those that need it.”

“Small things are important. A patient said, while looking at me in my PPE, ‘I recognise your eyes’.”

“A phone call on Friday afternoon, and, nine days later, the unit was up and running. A universe away from our previous work.”

“One Covid-19 patient stays in my mind. I was able to care for and stay with her until she died. She was 68 and we were her family. Helping her husband was so hard. This has made me more resilient but, at the same time, more compassionate to my ‘patient family’. Britain seems more compassionate. Oh, and I love The Clap!”

“Enjoy every day. Life is nothing; it can end so easily. Be kind and generous.”

“I feel emotional about my patients. I am strong at hiding my feelings from colleagues and family, but sometimes in the shower, at home, that’s when I cry. In normal times, I like doing patients’ hair, helping them shower, cutting their nails. Because of Covid-19 this wasn’t possible. But I tried to keep them comfortable, to moisturise their skin, to cry with them and to give their hand a little squeeze. I know I did the best I could for them all.”

“Many patients have had tracheotomies. I give them a voice, a means to communicate. On waking from sedation, we asked one patient what he would like to drink first and he whispered, ‘organic, M&S lemonade, please’. Always sticks in my mind.”

“I can’t sleep. What if I catch it and bring it home? [My family] say ‘don’t go,’ but I have to go. We argue, and I am in tears on the bus. My best friend died of Covid-19 in three days.”

“We found that many of our Covid-19 patients deteriorated faster than we could keep up with, and this was before we necessarily understood just how quickly the disease could affect them. I distinctly remember one woman who looked terrified, and it’s because she knew she was about to die. What still upsets me is how little time we had to make her comfortable.”

“So happy to see people going home.”

“When you are able to make a human corridor of applause for a patient who was supposed to die, it is something special. As one walked out, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘has her son put the dinner on?’”

“I’m no hero. I’m someone who’s lucky enough to work in the best profession there is for me.”

“I lost a friend and a family member to Covid-19. It is heavy, but you have to keep going. I wouldn’t do anything else.”

“Just now, my patient walked out of critical care to his physio. I was with his daughter; we watched him walk and his face turned to us – a great moment.”

“At the start of the pandemic, UCL took the decision to release all their clinical staff from academic and research responsibilities, in order to staff hospitals. This is all about teamwork, putting others first and doing the right thing. It is a vocation.”

“In our PPE, we must have looked like aliens to our patients. That was tough.”

“People are dying with no build up to death, no ability to have conversations and to say goodbye when they go into critical care. Even as a hardened professional, this has been difficult.”

“Fear, uncertainty, teamwork and collaboration.”

“I led the strategic incident management meetings, so I was painfully aware of the impact the virus was having on our patients, their families and our staff. But seeing the impact close up was very different. When I went to the wards to check in on our staff, I felt it – the temperature, the anxiety and the sights. Some patients were nursed in a prone position, face down to help their breathing. The inability to see their faces affected me greatly. I was angry with this virus, and could feel the weight of the concern and loss we bore on behalf of their families who were absent.”

“On my first shift in critical care, I looked after a patient whose wife was with him. Afterwards, when she took off her PPE, my hair stood on end – I recognised her as the wife of a dear friend from years ago who was now lying in the ward we had just left. Holding on to my emotions until I got home, I couldn’t stop crying.”

“In all my years of nursing, I have never felt so scared. There were parallel feelings of fear and duty. But I was so glad to be in the NHS for this experience. And to be among the fantastic medical minds at UCLH.”

“I am asthmatic and, walking in on the first day, I was so scared. I am more confident now.”

“I am scared, but I try to keep on working.”

“Now it is calmer, but when I walk through the wards I still see the faces of the patients from the peak. Some made it; others didn’t. I have flashbacks.”

“I am humbled. No matter who you are, you are affected by this disease. I am missing my cancer patients.”

“This is busy, demanding and you have to be on the ball. But seeing a patient who you thought was in trouble walk out of the ward, that gives you great pride.”

“It’s been hard, but we have all worked hard together.”

“I was so stressed to begin with. Now, I’m ok. It’s good to be appreciated.”

“Things that would normally take five years have been done overnight. All staff have shown such innovation.”

“15 months ago, I was a teacher. It’s tough now, but I’m so glad I changed.”

“The public reaction to the NHS was amazing. Sometimes you forget, and we needed that pat on the back. I want this to have a legacy.”

“It’s hard living among the dead on a daily basis.”

“I’m so happy to be here, even with Covid-19 about. I get true energy and happiness from my work, which I transfer to my family when I go home.”

“In the beginning, it was hard. We were watching Italy – where I’m from – and knew what came next. But we could prepare. We worked through history and it changed our lives.”

“I saw people dying almost every day. It has changed me. I am stronger, I am no longer scared of Covid-19.”

“It’s important for everyone to do their job.”

“When Covid-19 hit it awoke our compassion. We had become a bit desensitised.”